It’s hard to imagine modern American life without cars. They line our streets, crowd our highways, and fill every inch of our suburban driveways. We’re taught that they symbolize freedom and progress—the open road, the American dream. But what if cars are actually the plague of our modern society?

That might sound extreme, but a closer look reveals that our heavy reliance on automobiles has created a range of problems, from social fragmentation to environmental destruction. Cars are not just a mode of transportation, they’re a force shaping the way we live, often for the worse.

A Brief History

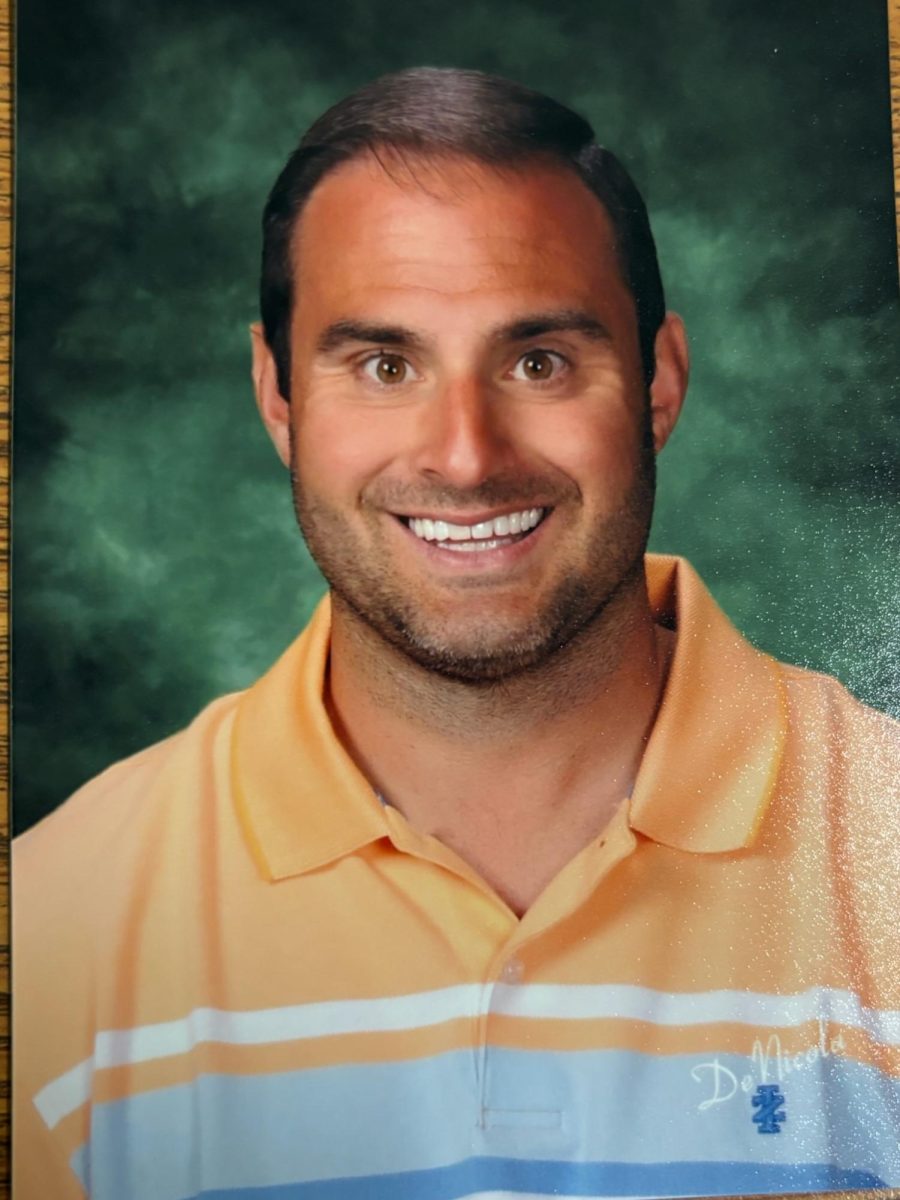

The story of America’s car dependency begins with a dramatic population shift. “In post-Civil War society, we see an influx of people moving to cities due to industrialization,” notes Mr. Anderson, the AP US History and AP Macroeconomics teacher. “By 1920, a majority of Americans lived in urban areas.”

But the post-WWII era brought a seismic change.

“Suburbanization really starts in the post-WWII era,” states Mr. Anderson. “World War II essentially lifted the US out of the Great Depression and created a surplus of wealth for the nation and many people, the foundation for America to become a car-centric society.”

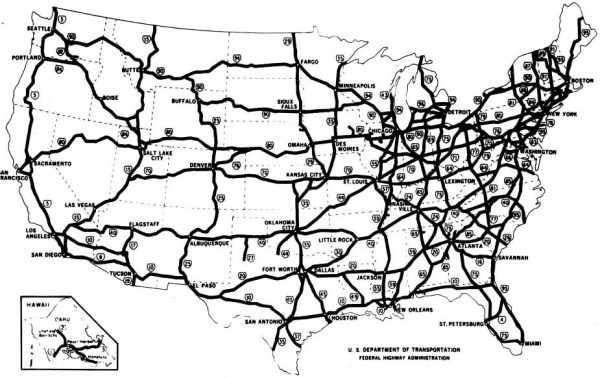

One of the major factors in creating a car-centric society was the development of the Interstate Highway System in 1956, which according to Mr. Anderson, “drastically enhanced the move to suburbs in WWII, led to a massive increase in reliance on cars, and drastically changed the structure of neighborhoods, essentially separating them.”

Although Eisenhower’s influence was the German Autobahn, unlike the Autobahn, the Interstate Highway System cut through many dense urban areas. Combining this with many acts that fueled the destruction of low income neighborhoods, the construction of the Interstate Highway System ultimately led to the displacement of many minority groups and low income families.

“Individuality was a huge factor for developing America into a car-centric society,” Mr. Anderson also notes. “The idea of driving wherever you want in a car became more appealing and aligned with American values of freedom and individuality, rather than having to share a bus or train with other people. As time progressed, the car became an iconic, inseparable symbol of freedom and the American Dream.”

According to Mr. Anderson, suburbanization began out of necessity due to a lack of housing, but eventually became more of a personal choice. People were drawn to the aesthetic appeal of suburban homes and sought refuge from crowded cities. By 1960, the majority of the American population had moved to the suburbs.

“With ‘white flight,’ much of the nation’s capital went to the suburbs, leaving the urban communities they left behind impoverished,” Mr. Anderson explained.

The Lethal Impacts

Cars have become so embedded in American life that their dangers are often overlooked or normalized. Yet beyond environmental degradation and social division, cars are also responsible for tens of thousands of deaths each year—many of them preventable.

According to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA), over 40,000 people died in motor vehicle crashes in the U.S. in 2023, marking one of the highest death tolls in recent decades. Among these, distracted driving played a major role, killing more than 3,275 people that year alone.

For Ms. Karen Torres, a distracted driving awareness advocate and founder of the organization ALL4UDAD, the consequences of inattention behind the wheel are painfully personal. Her father, Patrick Mapleson, was killed by a distracted driver in 2006. Since then, she has spoken out tirelessly about the irreversible consequences of momentary lapses in focus while driving.

“I think the most important thing is paying attention to the road,” Ms. Torres emphasized during her presentation to students at New Hartford High School on April 9. “Driving a car requires a person’s full consciousness, and taking your eyes off the road even for a few seconds is still dangerous. When you aren’t paying attention, you’re not just putting yourself at risk, you’re putting others at risk.”

Karen travels across the country speaking to high school students, civic groups, and lawmakers, often sharing her father’s story to put a human face on the data. Her mission is to transform attitudes toward distracted driving and build a culture of mindfulness behind the wheel.

“The only way you can prevent accidents is by paying attention,” Ms. Torres says. “Whether that means turning your phone off, putting your phone on driving mode or waiting to respond to a text—it can always wait.”

Her message is particularly crucial in a society where car use is not just common, but often necessary. The combination of sprawling infrastructure and lack of alternative transportation forces millions into vehicles every day, increasing both their exposure to danger and their potential to cause harm.

And the danger isn’t limited to drivers themselves. Pedestrian deaths have surged, reaching a 40-year high in 2022, with nearly 7,500 pedestrians killed in that year alone. Many of these deaths occur in poorly designed urban or suburban environments—places built for speed, not safety.

Whether it’s due to distracted driving, speeding, or simple design flaws, America’s deep-rooted car dependency continues to kill. It’s not just an environmental or cultural crisis—it’s a public health emergency.

Roads: Segregation By Design

One of the most overlooked consequences of car culture is how it has displaced people—physically, socially, and economically. Car-centric infrastructure has led to the rise of sprawling suburbs and massive highways that slice through urban neighborhoods. In the mid-20th century, entire communities, often low-income and minority neighborhoods, were bulldozed to make way for interstates and parking lots.

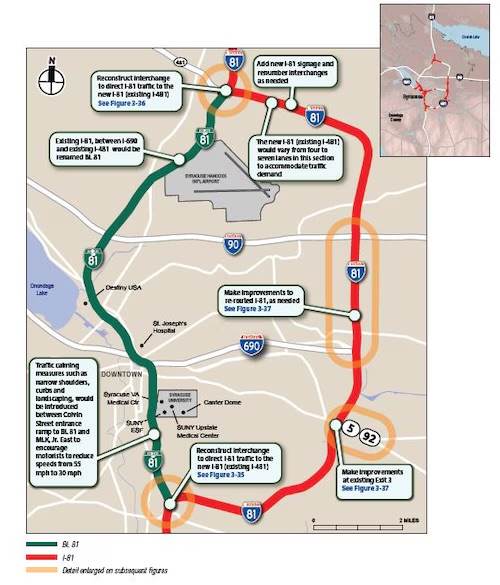

One city that saw huge displacement was Syracuse, N.Y., where the 15th Ward—home to 90% of the city’s Black population—was demolished in the 1950s to build Interstate 81, displacing 1,300 families according to the New York Civil Liberties Union.

Similar stories played out across the country. In Rochester, the construction of the Inner Loop destroyed hundreds of homes and businesses, including historic landmarks like the Lewis Henry Morgan House, a hub of 19th-century intellectual activity, according to the University of Rochester.

In New York City, the Cross Bronx Expressway displaced between 40,000 and 60,000 people, gutting working-class neighborhoods and leaving behind a legacy of pollution and division. This led to the property value in the area plummeting and as a result, the white community left the neighborhood and minorities stayed due to redlining or other racist housing policies.

Today cities are designed around cars, not people. Sidewalks are narrow or nonexistent, public transportation is underfunded, and biking is often dangerous. The result? People are forced into cars just to go about their daily lives, whether they want to or not.

“Many residential streets in New Hartford do not have sidewalks, but they were intentionally designed this way,” notes Mr. Prokosch, the AP European History teacher. “In addition to redlining, many planners purposely designed streets to not have sidewalks, which creates a barrier for people of lower socioeconomic status from entering these new neighborhoods.”

The construction of residential neighborhoods without sidewalks became a virtual barrier between communities, as many minority groups were unable to afford the luxury of a car in post-WWII America, leading to increased poverty in dense urban areas while the suburbs flourished.

A Society Split by Steel

Car dependence also keeps society separated, quite literally. Wealthier communities enjoy cleaner, quieter roads while poorer neighborhoods suffer from higher pollution, noise, and traffic accidents. In Syracuse, Black residents living near I-81 faced higher asthma rates due to traffic pollution according to NYCLU. And for those who can’t afford cars, the isolation is even more severe: 45% of Americans have no access to public transportation, making car ownership a necessity rather than a choice according to the American Public Transportation Association, 2023.

The “freedom” that cars promise is, for many, a mirage. For the elderly, disabled, or low-income individuals, car dependence is actually a form of restriction—a system that locks them out of jobs, healthcare, and even grocery stores.

The Environmental Toll and My Experience

The environmental cost of our car addiction is staggering. Transportation is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions in the U.S., accounting for 29% of total emissions according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Our reliance on cars is also fueling unsustainable resource consumption: the U.S. burns through 20 million barrels of oil per day, nearly half of which goes to transportation according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration.

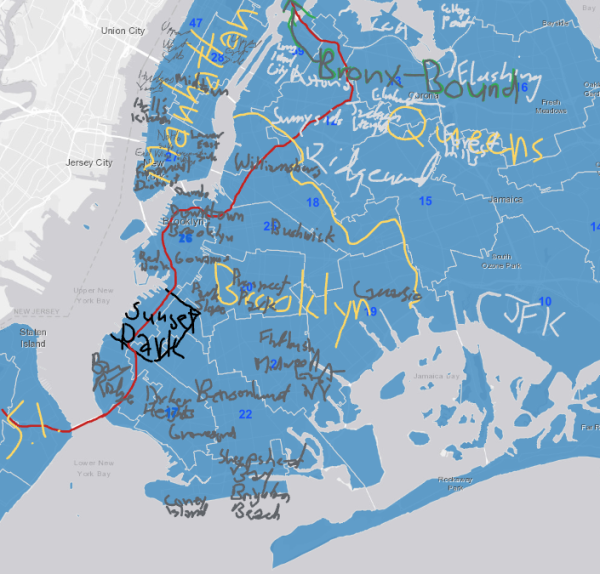

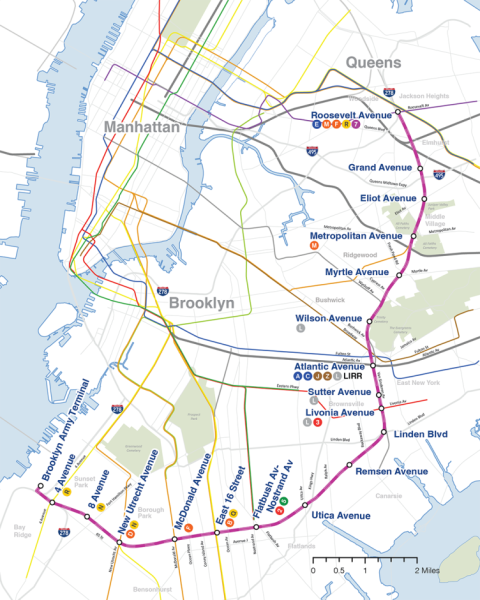

Highways like the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway (BQE) have left a trail of pollution and displacement in their wake. The BQE, which displaced tens of thousands of people, carved a 15-mile gash through some of Brooklyn’s most vibrant neighborhoods, leaving behind choked streets and divided communities. Even electric vehicles, while a step forward, don’t solve the core issue: a society built for cars, not people.

This was especially true for me as a kid, who lived right next to the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway. I remember living in eastern Sunset Park, on the intersection between 7th Avenue and 65 Street, having to constantly walk around the entrenched BQE (I-278), just to get to and from my school in Bay Ridge. Luckily, we were able to relocate closer to the school on 6th Ave and 65th Street in Bay Ridge, but became more disconnected from the Fuzhou Chinese Community on 8th Ave.

The damage of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway was not limited to my commute; it also drew an artificial wall through Sunset Park, separating the communities. Although this portion of the expressway was on an elevated viaduct, it has created an unprecedented amount of traffic in the area where even crossing 3rd Avenue can be a nightmare. The traffic is predicted to get worse in Downtown Brooklyn and be diverted onto the streets after its inevitable closure to accommodate for the deteriorating, decades-old triple cantilever due to repeated weight violations and extreme weather conditions.

Google Street View of the BQE Triple Cantilever

On the west side of the expressway, you’ll find one of the most vibrant Latino communities in the borough, but on the east side, you’ll find Brooklyn’s first Chinatown on 8th Avenue, home to the Fuzhou community.

The cultural divide can be seen with the drawing of New York State Senate District Boundaries. Instead of Sunset Park being part of one district, the east and west are divided among two districts. The eastern portion is compiled into the 17th District with Bath Beach, the north eastern corner of Bay Ridge, Kensington, east Dyker Heights, Bensonhurst (Brooklyn’s second Chinatown after Sunset Park), and Gravesend, which have a high Chinese population. The western portion is part of the 26th District, which includes Carroll Gardens, Cobble Hill, the Columbia Street Waterfront District, Dumbo, west Dyker Heights, majority of Bay Ridge, Fort Hamilton, Gowanus, Park Slope, Red Hook, and South Slope.

A Sense of Isolation:

Modern suburbs, designed exclusively for cars, have become prisons for children. The average American child now spends just 4-7 minutes daily in unstructured outdoor play, compared to over 7 hours in front of screens according to the Nation Recreation and Park Association.

But it isn’t just in children. Think of the last time your family had to go out to get groceries, go to a doctor’s appointment, or go out to eat. You had to get into a car. Nobody expects someone walking along Higby Road just to get to Walmart. The intentional design of separating residential neighborhoods and commercial districts has directly created a hassle for the common suburban family.

Today, children have lost the right to independently navigate their neighborhoods. When every errand requires a car trip, parents become chauffeurs, and kids lose the critical life skills that come from walking to school or biking to a friend’s house. Studies show that only 13% of American children now walk or bike to school, down from 50% in 1969, according to Safe Routes to School. All of this is a direct consequence of communities built without sidewalks, with dangerous arterial roads, and with schools placed deliberately far from homes to accommodate large catchment areas.

Cellphones, combined with American suburbanization, have also worsened the issue. Social media in a way has also decreased genuine human interaction with artificial interaction, combined with suburbanization has created a sense of social isolation, contributing to a decline in mental state, especially from Gen Z.

But this issue seems to plague the U.S. more than any other country, with Mr. Prokosch stating, “During a visit in Italy I saw high school students hanging outside, talking face to face without the presence of cellphones, and it shocked me since you don’t see that behavior in the US. If you were to walk out into the hallway in the morning, you would see that most people are talking in groups while on their phones.”

This could be due to the well-planned neighborhoods and the overall higher population density commonly seen in Europe, as even small towns are easy to navigate by walking, allowing people to interact with each other easier.

In addition, the sense of isolation created by suburbanization and cell phones have also contributed to an increased obesity rate. In 2022, the U.S. was ranked the tenth most obese nation, with an obesity rate of 41.64% according to the World Obesity Observatory.

The Gentrification Paradox

After the turn of the millennium, cities have seen a return of young people due to their preference for the urban environment. This trend has contributed to the revitalization of many inner-city neighborhoods that had previously experienced decades of disinvestment. The draw of walkable communities, public transit access, cultural amenities, and proximity to employment hubs has made urban living especially attractive to millennials and Gen Z.

However, this demographic shift has coincided with accelerating gentrification processes.

“Gentrification is the process in which a poor urban area is changed by wealthier people moving in, improving housing, and attracting new businesses,” Mr. Anderson notes. “Although some welcome the reinvestment, it may end up displacing the low-income residents in the area and driving up local property values and rent, ultimately creating a housing crisis depending how and where it is implemented.”

Neighborhoods once marked by economic disinvestment have transformed into trendy enclaves, often resulting in rising property values and rent prices. For instance, a 2019 study by the National Community Reinvestment Coalition found that more than 135,000 residents, mostly low-income people of color, were displaced by gentrification between 2000 and 2013 in just 20 U.S. cities with Washington, D.C., San Francisco, and New York were among the most affected.

Another World

To understand just how deeply cars have shaped life in the United States, it’s helpful to look elsewhere—at a world where cities were built before the car, not around it. As Mr. Prokosch, the AP European History teacher, explains, “Most European cities have more narrow streets than American ones, simply because they were founded and built without the automobile in mind. In Siena, Italy, the streets are so narrow that you can barely fit a Toyota Prius”

European cities often originated based on natural geography and trade, not car access. “Many were founded near a major water source, or near a major port, near a trade route, and economically important,” Mr. Prokosch adds. “For example, Siena, Italy was founded right on the Via Romana, a major trade route from Rome to Northern Europe. As time progressed, Siena grew and became a major trade stop.”

Similarly, St. Andrews in Scotland rose to prominence as a major fishing city—walkable by necessity, not design.

Because of this older, denser layout, European cities simply never adapted to the sprawling road systems seen across the U.S. Instead of retrofitting their cities for cars, many European countries chose to double down on public transportation and walkability.

Driving itself is also viewed differently. “The car is not like a staple of life like in the U.S.,” says Mr. Prokosch. In Europe, obtaining a license isn’t taken lightly. “You must be 18 to obtain a license, with a minimum of 20 driving hours, and over 2,000 euros to apply.”

The cost and effort required to drive—combined with the availability of high-speed trains, trams, buses, and bike lanes—makes car ownership feel more like a burden than a necessity.

Indeed, in cities like Vienna, Berlin, or Copenhagen, you’re more likely to see residents hopping on a bike or tram than sliding behind the wheel of a car. These systems are well-funded, integrated, and accessible. As a result, people live closer together, rely less on private vehicles, and interact more with their communities.

While the U.S. has long operated under the assumption that cars equal freedom, Europe shows us a different reality—one where freedom comes from not needing a car at all.

The Road Not Taken

But it doesn’t have to be this way. Many cities across the globe have shown that it’s possible to break free from car dependency and design communities that prioritize people, not vehicles. From integrated public transit to pedestrian-first infrastructure, these cities offer a glimpse into a future where streets are for people, not just traffic.

Shanghai, one of the world’s largest megacities, has managed to build an extensive and efficient public transit system that serves over 10 million riders per day. With 830 kilometers of metro lines as of 2023—the longest subway network in the world—Shanghai has prioritized rapid, reliable, and accessible mobility options that reduce the need for car ownership in its dense urban core. In many neighborhoods, it’s easier and faster to take the metro than drive.

Zurich, Switzerland, is a gold standard for how a mid-sized city can operate virtually car-free. With a network of trams, buses, and trains operating in perfect sync, Zürich has implemented policies that discourage car use through limited parking, strict traffic control, and investment in walkability. Nearly two-thirds of trips in Zurich are made by public transport, biking, or walking, according to the city’s mobility report. The result is a quieter, safer, and healthier urban environment.

Amsterdam is perhaps the most famous example of a city built for bikes rather than cars. Over 60% of trips in the city center are made by bicycle, thanks to decades of infrastructure investment, traffic-calming policies, and a cultural embrace of cycling. Amsterdam wasn’t always this way—in the 1970s, it was car-clogged and dangerous, but grassroots activism and smart urban planning transformed it into the world’s most bike-friendly city.

Even in towns of the Greater Accra Region in Ghana like Mataheko and Afienya, where it is somewhat car-reliant, it has still implemented mass-transportation with private owned “trotro buses” that operate on specific routes frequently. Not only this, but the towns have also been able to create a society where a car isn’t needed to run necessary errands like getting groceries, by only having to go to local street vendors, according to David Amankwah, a junior at New Hartford Senior High School who is originally from Ghana.

These cities didn’t get there overnight. They made deliberate, sometimes difficult choices—limiting car access, raising fuel taxes, investing in public infrastructure, and most importantly, designing cities for human connection rather than automobile convenience.

While the U.S. faces unique geographic and political challenges, these international models prove that transformation is possible. They show that urban life can be vibrant, clean, connected, and safe without needing a car for every trip. It’s not just about transportation—it’s about redefining what makes a city livable.

A Bright Future?

Although our society has faced severe setbacks, there are signs that a new urban era may be emerging—one where cities prioritize people, not pavement. Cities such as Rochester, NY, are actively reclaiming the land once lost to car-centric infrastructure and trying to undo decades of damage.

In Rochester, the city filled in a section of its Inner Loop expressway, transforming it into a walkable, mixed-use development. What was once a dividing trench of concrete is now reconnecting communities, attracting businesses, and adding affordable housing. The project is so promising that Rochester is moving forward with plans to fill in the northern portion of the loop as well.

Just down the Thruway, Syracuse is undertaking one of the most ambitious urban freeway removal projects in the country. The I-81 Viaduct Project will demolish a crumbling elevated highway that for decades split the city and displaced thousands—especially in the historic 15th Ward, once home to 90% of the city’s Black population. Instead of rebuilding the viaduct, the state plans to replace it with a “Community Grid”—a network of surface streets designed to restore neighborhood connectivity, reduce traffic, and promote economic development. Advocates hope this will be a transformative moment of restorative justice for Syracuse.

Although New York is the most pedestrian-friendly city in the United States, its reliance on cars is still apparent. However the shift away from car dominance is also gaining momentum. One of the most transformative efforts is the Fifth Avenue redesign project, which is turning one of the city’s most iconic car corridors into a pedestrian-friendly, transit-prioritized boulevard. Stretching from Bryant Park to Central Park, the project features expanded sidewalks, dedicated bus and bike lanes, and aims to make the avenue a world-class public space. The goal is to put “people over vehicles,” according to city planners.

New York City is also investing heavily in public transit. Projects like the Second Avenue Subway expansion, the Interborough Express (IBX)—a rail line connecting Brooklyn and Queens. At the same time, congestion pricing has launched this year, charging vehicles entering Manhattan’s central business district and using the revenue to fund public transportation improvements. Overall, the congestion pricing plan has seen significant improvements in traffic reduction, but has also experienced fierce resistance from many commuters and the Trump Administration.

Across the country, cities are beginning to reclaim streets and rethink infrastructure. In Los Angeles, a city synonymous with car culture, transformation is underway. Projects like the Rio de Los Angeles State Park and plans to convert sections of the 710 Freeway corridor into green space and multi-modal transit routes show a dramatic shift in thinking. LA is also investing billions in expanding its Metro Rail system, adding bike lanes, and prioritizing bus lanes to combat traffic and carbon emissions.

At the federal level, initiatives like the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act passed by the Biden-Harris Administration and Reconnecting Communities Program are dedicating billions of dollars to help cities improve public transportation, dismantle outdated highways, and heal the urban scars they left behind.

Although the United States has made significant progress in improving urban infrastructure, some still remain pessimistic.

“I don’t think we’ll see any major developments in the future,” notes Mr. Prokosch. “America made its choice to be a car-centric society in 1956 with the passing of the Federal-Aid Highway Act.”

In addition, with polarization of politics, passing infrastructure and urban reclamation bills become increasingly difficult.

However, some still feel hopeful about the future, with Mr. Anderson adding, “Although I don’t think there will be much change in the near future, it will come with time, and it will be interesting on how they address these issues in the future.”

Like all wounds, they heal with time—if given the care and attention they need. The scars left by America’s car-centric past are deep, but they are not beyond repair. From the rebirth of neighborhoods once dissected by highways to the reimagining of streets as spaces for people, not just vehicles– the future holds promise. It won’t be easy, and it won’t happen overnight. But as more cities begin to center equity, sustainability, and community in their planning, we edge closer to a world where the American landscape is no longer defined by asphalt and isolation—but by connection, resilience, and shared space. The road ahead may still be long, but at least now, we’re starting to walk it together.