This story was originally published in October 2023. It was republished here digitally in November 2024.

In 2017, Tarana Burke shared her experience of assault online with a simple hashtag –#MeToo –pointing out that she and millions of other women had experienced the same violence and that they just didn’t talk about it. The aftermath of which has produced astronomical consequences for the world.

The #MeToo movement and the #TimesUp movement (a similar concept specific to Hollywood) both showed that survivors were not alone and that the violence of patriarchy was, unsurprisingly, systemic.

As of late, however, the campaign seems to have created less of an impact than we originally thought. In the past year, the over abundance of public instances have proved that men are still not being held accountable for their actions and women are still being put at extreme risk.

Perhaps most notably, Luis Rubiales, the former president of the Spanish Soccer Federation, publicly kissed player Jenni Hermoso without her consent after the World Cup Final and chaos ensued. Rubiales has refused to apologize, even after resigning, citing his reason for leaving as his “family was hurting” (The Guardian) from all the attention, not that he had assaulted a woman in front of the entire world.

This resignation came approximately a month after the entire world saw what happened on live international television and weeks of Rubiales refusing to admit any wrong doing.

Similarly, it was reported in USA Today that Mel Tucker, a former college football coach that was fired after serious allegations of abuse, made millions of dollars while waiting for the college to decide if they were going to fire him or not.

Mason Greenwood, a former Manchester United and English national team player, was recently accused of assault and after the allegations were made public, Manchester United decided this was not a violation of his contract, ESPN reported. The club and Greenwood have mutually parted ways at this point in time but Greenwood has already signed with a new club in Spain where he was “warmly welcomed” (The Guardian).

These instances demonstrate how women are still being systematically abused, violated, and silenced, and they’re only the ones in the public eye.

I would like to make clear that I don’t think carceral punishment would be any real solution, due to their oppressive and circular nature. Prisons often fail to deter crime and simply place those accused in awful situations.

As Tarana Burke said in her piece for Time, “For decades, there have been laws against sexual violence. There is no evidence that carceral solutions are actually working.”

The goal is not for these men to be punished, but for women to feel safe and respected which is not currently happening. It isn’t respecting the women when their oppressors are constantly being given excuses for their behavior, which is why I mention the men above and the lack of consequences faced they faced.

Instead of prison, the solution is advocating for structural change. This could be protesting, community building, or just simply letting the people around know that you’re their for them if anything ever happens. Change as systemic as this takes time, but that doesn’t mean it shouldn’t be fought for and it’s certainly worth being patient.

The cycle of social awareness without concrete change isn’t new to movements like #MeToo and #TimesUp.

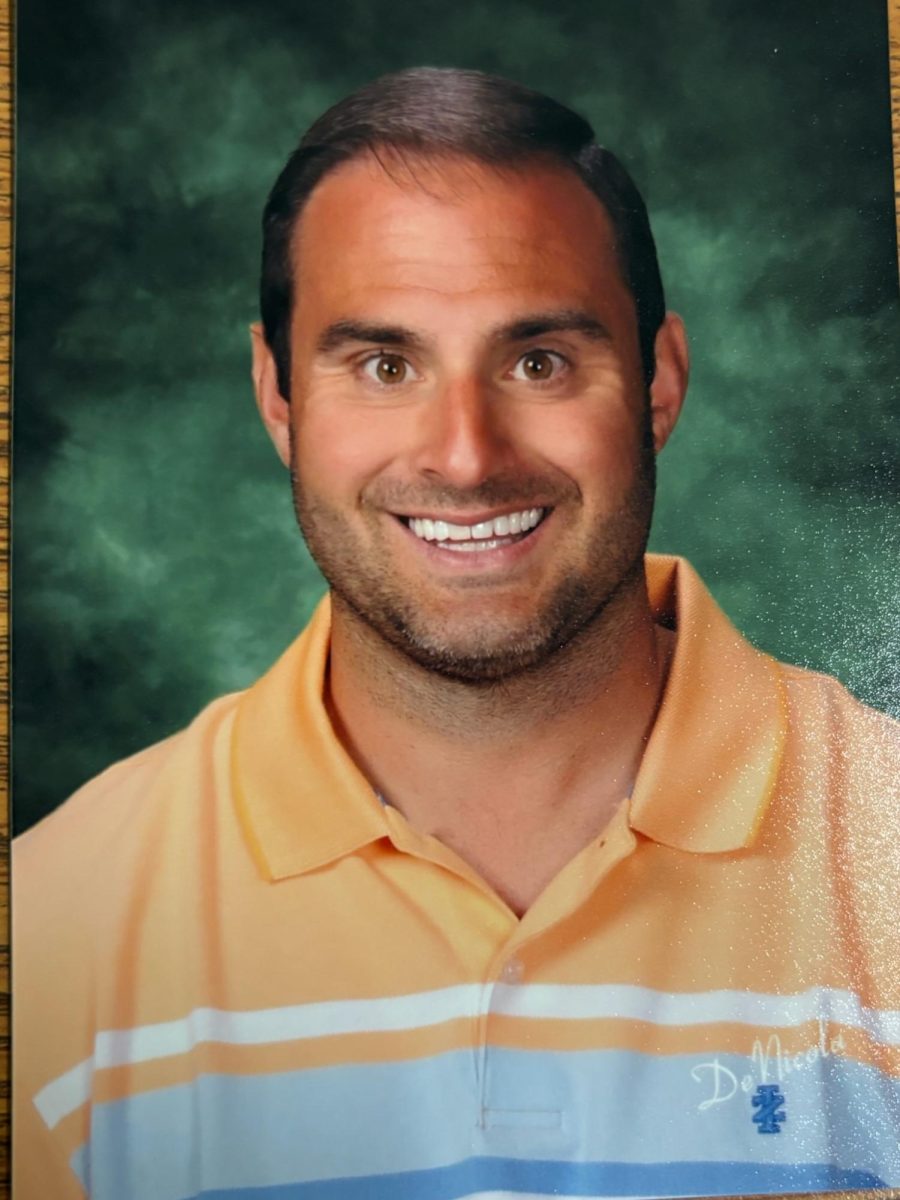

Ms. Nugent, an English teacher from the high school, recalls marching in “take back the night” walks over twenty years ago and in 1991, Anita Hill testified in front of a congressional committee in charge of confirming Judge Thomas into the Supreme Court.

Hill had to describe the abuse she and other women suffered while working for Thomas in the Department of Equal Employment Opportunity (the irony is not lost on anyone).

In the end, Thomas was still confirmed, but Hill’s testimony was thought to be a turning point for those fighting for equality in the work place. Suddenly the whole country was talking about workplace harassment and it seemed like the problem would be solved.

Flash-forward twenty-six years to 2017, when the first New York Times article detailing abuse in the film industry was released and Tarana Burke made her first #MeToo tweet. The Oscars had #TimesUp as a theme for the ceremony that year, powerful people lost their jobs, and everyone was talking about how to end the systemic abuse of women.

There was even an almost repeat of the Anita Hill trial when Christine Blasey Ford came forward with allegations against Judge Kavanaugh before he was confirmed into the Supreme Court. Surely, change was going to follow.

But how much really has changed?

In an interview, Ms. Nugent, shared her perspective on the issue.

“I remember men around me saying incredibly horrible and disrespectful things about [Anita Hill]. I’m not sure that things have changed much. Consider how people treated Christine Blasey Ford when she took the risk of telling her story about Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh,” she said.

We’re still here. Women are still being abused. But how, if everyone is aware of the problem, perhaps even more so than when Hill testified, why is it still happening?

Debra Katz, a lawyer for Blasey Ford, told Jodi Kantor and Meagan Twohey at the New York Times, “Things have quantitatively changed… [but] The institutions have not changed. The Senate has not changed”.

Without the systemic transformation of these oppressive institutions, no real change is going to occur. We will just stay in this cycle of every twenty-or-so-years there is a big public conversation about abuse that end without anything changing.

But that isn’t what has to happen. We don’t have to keep doing this every twenty-five years. We don’t have to keep suffering this abuse.

Burke wrote in her Time piece about the shortcomings of the movement, from not being inclusive enough to being reduced to a societal joke by men. But she also wrote that we don’t have to let it be reduced to that. It isn’t the movement’s fault, necessarily; it’s the fault of the institutions that preserve and perpetuate patriarchy, racism, and homophobia and transphobia.

People have to continue to call out poor behavior and take care of survivors, even though sometimes it may feel useless, or uncomfortable because, in the end, its the only way we can advance the movement.

She writes, “The #MeToo movement is what we make it… it’s how we take responsibility for creating a world without sexual violence; and how we respond to the needs of the survivors who are already here.”

Ms. Nugent notes how maybe the movement didn’t do enough to emphasize women’s autonomy and empowering them. Our generation can make that alteration and can use our power and our autonomy to force this issue, to mutually support each other, and to create a community where women feel safe.

A community where women can speak about their experiences without being questioned as liars, or judged for their bravery; where men aren’t allowed to keep getting away with abusive behavior; and where we’re able to support one another without prejudice.

The culture won’t change if we don’t force it to. And we must force it to if we ever want to protect ourselves and each other.